Author’s Note: Each academic year, the Griot Institute identifies a question or issue of interest that’s central to the continued study of Black lives and cultures and develops a series of programs to explore these questions from multiple disciplinary perspectives and dimensions. The theme for this year is “Joy: Centering and Embracing the Fullness of Black Humanity” and this blog post highlights the campus lecture of T. Oliver Reid, an accomplished cabaret artist, director/choreographer, film and television actor, and co-founder of BLACK THEATRE COALITION. He delivered his lecture on Wednesday, February 28th at 7:00 PM in the Elaine Langone Center.

A multi-hyphenate veteran of the entertainment industry, T. Oliver Reid graced the Elaine Langone Center forum on Wednesday, February 28th, offering insights, inspiration, and a celebration of Black joy – the Griot Institute’s theme for this academic year’s lecture series.

He prefaced his evening lecture about Black joy with the following: “This idea of joy for me has been a lifetime of figuring out what it means to me. I am no expert on joy.” Hearing someone admit this outloud – the seemingly elusive and ephemeral nature of joy – immediately set a tone of authenticity and vulnerability for the evening’s discourse. Moreover, it reassured the audience – myself included – that having trouble defining joy doesn’t mean you don’t know it when you see it (or experience it). Reid spent the opening moments of his lecture demonstrating this exact point as he propped against the table, iPad in hand, and hopped from one Google definition to the next about joy.

“Joy, a noun: a feeling of great pleasure and happiness.”

“Pleasure, a feeling of happiness, satisfaction, and enjoyment.”

“Happiness, a state of happy being.”

“Happy, feeling or showing pleasure or contentment.”

…you get the point.

In an attempt to unravel the tautology of joy, and take us with him as he did so, Reid asked us a series of questions: (1) what does joy feel like; (2) how do you express joy; and (3) is Black joy different from joy in others? Most intriguing to me in hindsight is the last question, and here’s why.

During spring break, I had the opportunity to go on a week-long trip to Oklahoma as part of the Office of Multicultural Student Services’ annual Civil Rights Alternative Spring Break Trip. Each day took us to a new Black town, but on Sunday, March 10th we found ourselves in Tulsa, Oklahoma – home to Black Wall Street.

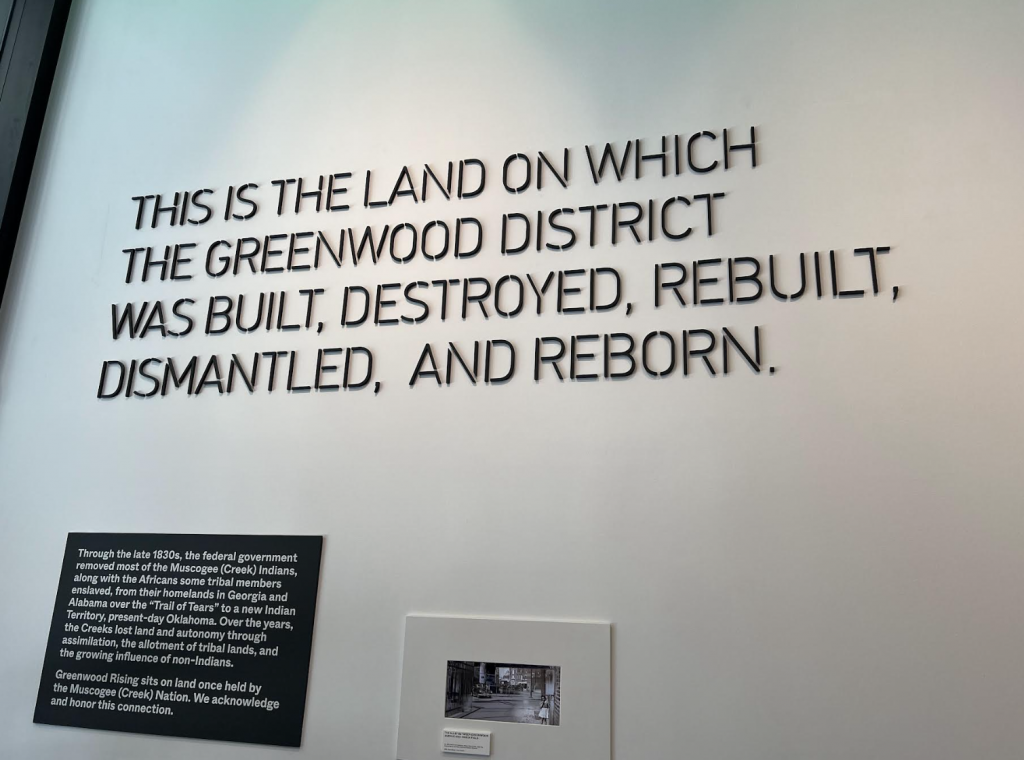

We toured the Greenwood Rising Museum – an “award-winning, world-class history center that tells the story of Tulsa’s Historic Greenwood District,” including “the story of the formation and success of Black Wall Street,” “national context of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre and the story of the Massacre itself,” “the second Greenwood District decline,” and the potential of reparation and reconciliation. I personally spent the most time in the section of the museum called “Arc of Oppression — Systems of Anti-Blackness” which provided historical, social, and political context for what happened in Tulsa in 1921. Note: for more information about the Tulsa Race Massacre, visit the Greenwood Rising Museum website or “What the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Destroyed” published by The New York Times.

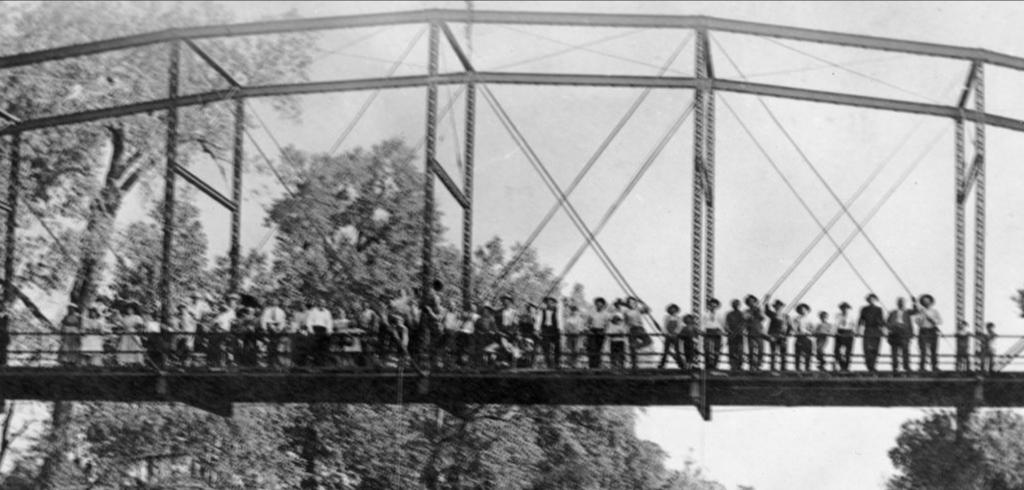

One of the panels in the “Arc of Oppression” gallery had a picture of the lynching of Laura and L. D. Nelson, a Black mother and son extrajudicially targeted by a white mob for the alleged murder of a white Oklahoma deputy. Note: for more information about the lynching of Laura Nelson and her son, visit this article by the Equal Justice Initative. I would later see this same photo on campus in my Black Women’s History course with Professor Cassie Osie (you should read my interview with her, by the way).

While the topic of discussion in class wasn’t necessarily joy, it did come up. White joy, specifically. We were discussing the foundational role lynching played in the shaping the contours of the Reconstruction-era in the United States, and, more pointedly, how lynching was deployed as a tool of degradation, control, and domination by some white people. We flickered through various photos of lynchings, paying particular attention to not the victims themselves, but the perpetrators: white men and women of all generations and ages, of all social class standings. Folks who were presumably mothers, fathers, grandparents, children, aunts, uncles, pillars of the community, and regular ordinary people, treating the lynching of Black men and women as a spectator sport. This includes the lynching of Laura and L. D. Nelson.

When prompted to share our musings about the photos, in relation to what we had been learning about Reconstruction and lynch law, several of my classmates noted that the white people in the photos – the audience, the perpetrators, the onlookers – seemed to be enjoying the spectacle. As a throwback to T. Oliver Reid’s lecture, it seemed as though they derived varying degrees of pleasure, happiness, contentment, and satisfaction from their acts of gratuitous violence.

Recalling Reid’s prompting, “is Black joy different from joy in others,” I say yes. Unlike white joy – the joys of whiteness – Black joy isn’t rooted in the “wielding [of] absolute power over abject and dehumanized victims” or “the visual consumption of the black body in pain” (Anne Rice, “How We Remember Lynching”). Black joy is…well, that’ll take another blog post to flesh out. My blog post on Tracey M. Lewis-Giggetts’ visit to campus is a good place to start.