About the Author: Ninah Jackson is a junior at Bucknell University, double-majoring in Education and Critical Black Studies. In addition to being an intern with the Griot Institute, she is the Chief of Staff of the Black Student Union, a Humanities Fellow, and a co-facilitator of the Social Justice Learning Community course.

As we embark on a new semester here at Bucknell, myself and the other interns at the Griot Institute are thrilled to launch a special series highlighting faculty on campus whose work aligns with the mission and vision of the Institute! ✨

This inaugural spotlight is an excerpt of an interview with Dr. Cassie Osei, an Assistant Professor of History who specializes in the history of Latin America, African Diaspora, and modern Brazil. This interview was conducted in November of 2023 and has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

Ninah Jackson: I would love for you to first introduce yourself with whatever you feel is pertinent!

Prof. Osei: My name is Dr. Cassie Osei. I am an Assistant Professor of History at Bucknell University. This is my third semester, so I’m new faculty. I earned my Ph.D. in History from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, specializing in Latin American history with a focus on the African diaspora, specifically in Brazil. I teach classes here on Latin America, broadly. So, that includes survey classes on national histories like Brazil, Mexico, Cuba, as well as broad-based surveys.

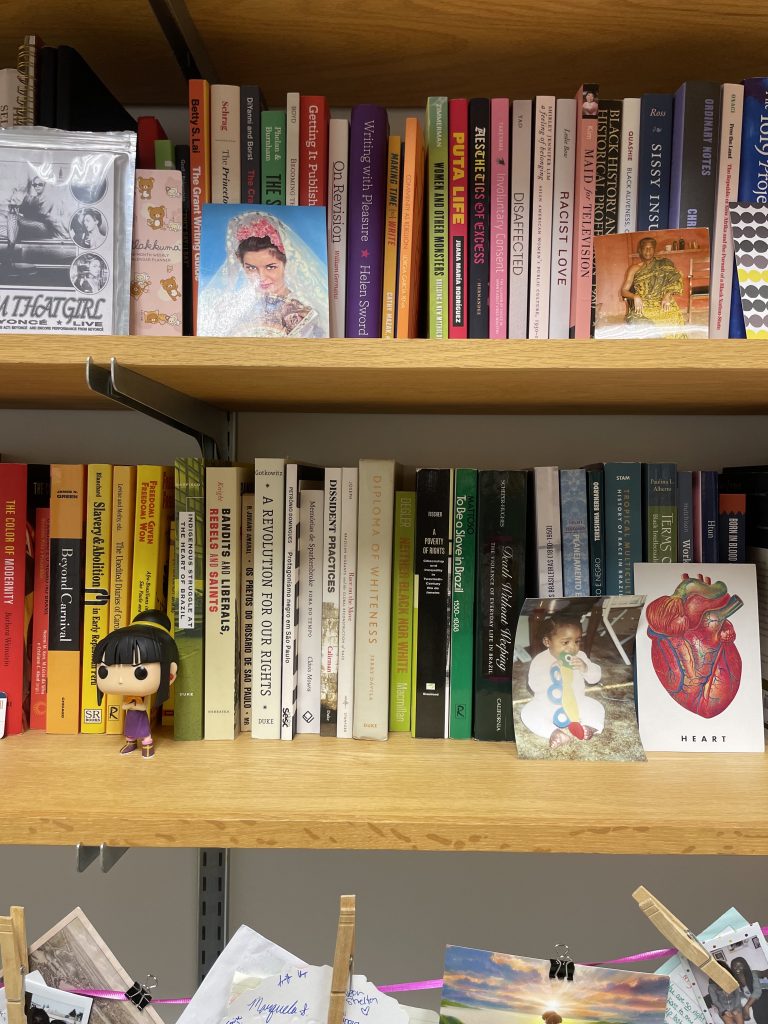

I also teach thematic courses relating to my expertise and the Black experience in Latin America and gender and sexuality, but also courses such as U.S.-Latin American affairs. My first course that I taught here was called “Bullets, Bananas, and Bad Bunny,” which was training students to think about U.S.-Latin American entanglements through the commodities of drugs, fruits, and pop culture, such as Bad Bunny and the reggaeton boom. I am currently preparing a book manuscript about the history of Black domestic workers in Brazil in the 20th century.

My personal profile is that I am the daughter of West African immigrants from Ghana. I’m the first child to be born in the United States, to go to college, to get a Ph.D., a master’s, and become a college professor. I am from the Midwest, Kansas City, Kansas, the same place as artist Janelle Monáe! I am a nacho queen connoisseur. I love dancing. I love video games. I love cooking.

Ninah Jackson:Can you share a bit about your journey into academia and how you developed your specific focus on Latin America, the African diaspora, and Brazil?

Prof. Osei: Earlier, I said that I was born in Kansas. Kansas is a state that has this mythology about itself because of the Civil War. So there was the Bleeding Kansas conflict; people from Missouri tried to influence whether Kansas would be a free state or a slave state coming into the Union, because it was previously a territory.

There were all of these skirmishes, bloody skirmishes. They burned down Lawrence, which is where the University of Kansas is at and where I went to school for my undergraduate. There’s a man who looms large. His name is John Brown. He goes to the slave capital of Kansas, and there is a bloody massacre. It’s called the Pottawatomie Massacre. In elementary school, I was taught that people’s heads were chopped off, which is likely an exaggeration, but the exaggeration is a throughline to our state myth: that we were steadfast in our opposition to slavery. We’re very proud of this legacy of being fiercely anti-slavery, but that does not mean that we were anti-racist or that we loved Black people. As a child, I was very cognizant of that, even though I didn’t have the language to describe that. I grew up in the ’90s, which was a very particular time, so I had this notion of anti-Blackness without having the language.

In the fifth grade, I was assigned to Ida B. Wells for my American Heroes Project. And actually thinking about that, that was an iconic moment, not only because of Ida but also because we had to learn to sing Mariah Carey’s “Hero,” and we had to recite it. I fell in love with African American history. Like I don’t say take this lightly, but it was like life saving for me. It was finally a language and an embodiment that I could take on that affirmed me as a person in ways that school could not.

And, you know, despite having these Black parents from Ghana, they couldn’t fill in the gaps that I needed, the context that I needed. I go to college; I was supposed to do pharmacy, and I flunked out of school. Like, I literally got kicked out of school.

My parents were like, you know, incensed. But I met somebody and she was like, ‘Well, you obviously don’t even want to be a pharmacist. What do you want to do?’ I want to be a historian, so she talked to my parents. She was Ghanaian, too. She’s currently at Howard now. Her name is Elisabeth Asiedu.

I owe my entire life to that woman. That’s why I’m an academic. Anyway, in history you need to pick a language. I learned French for seven years because my parents lived, or not my parents, my dad’s family lived in France. They migrated out of Ghana to France. I lived with them for a bit as a high schooler.

I hated France because I was like, they’re anti Black. And specifically anti African and Arab. So, I was like, I’m not doing French no more. And so I just randomly chose Portuguese because I expected I’m going to learn Black history, post civil rights…I don’t need a language, which is not true.

Even African, African Americanist, Americanist, they do need languages. It should be encouraged because it opens you up to the entire African world, Black world, right? You need Portuguese. You need French. You need Spanish. And I did, in addition to indigenous languages, Yoruba, Twi, Swahili, Creole, et cetera, et cetera.

So I enrolled in two courses at the same time: intro Portuguese and another class on the history of Black people in modern America in the colonial period. And in one class I was getting this language about, oh, we’re a multicultural society and then the other, towards the end of the class, I learned Brazil was the last country in the Western Hemisphere to end slavery. 1888.

I got a fellowship from the government to go study abroad in Brazil for free. I came back, I was like, do I want to study the U. S. or Brazil? Because I want to be an academic and the job market in history is devastating. It’s very bad and it’s worse for Americanists.

So it was like, ‘I’ve learned Portuguese. I’m just gonna do Latin America.’ And just to conclude, in grad school, when I first started, I was invested in Brazil, Black Brazil, because I wanted to learn more about myself. But eventually, it transfigured into, this is worth studying for its own reasons outside of myself. And as a citizen, not of the United States, but of a global Black world, I should be invested in Brazil on its own terms. I should be invested in these Black people on their own terms. And especially being somebody who had read Black Brazilian feminist theory, that became more and more compelling.

Ninah Jackson:How has your research and areas of focus evolved over time? Additionally, what are some of the key findings or insights that have emerged from your work?

Prof. Osei: It’s very interesting because when I applied to my PhD program, I proposed, as my dissertation project, to study Black women and the ways in which their images are used within the wider Black movements and how they are obscured and tropified…even though Black women are the ones carrying these movements forward, decade by decade.

And then, you know, a lot of the work on Black Brazil emerges from the study of race relations primarily. So, I was training myself—well, I was being trained in that. One of the things I kept writing papers about was the 1988 constitution and how Black people were pivotal in trying to make it happen.

My advisor just set me aside and said, ‘Cassie, have you noticed that you’re writing about Black women, but you don’t actually have a gender analysis?’ I was like, ‘What do you mean?’ He explained, ‘You’re not engaging the fact that women are doing a certain thing and men are doing another thing.’ I found that fascinating. [00:17:00] The through line to that is to explain how my research has evolved in grad school. You come with an idea, but you’re also being trained in skills that, at times, prevent you from seeing your vision through. You have to learn methodology, literature, and be conversant in all these things. You have to get a helm on technique and skill. You have to hone your craft. And so, I struggled a bit with gender analysis all the way through to my dissertation.

Ninah Jackson: What are some moments of triumph or breakthrough that you’ve experienced in your academic career, in the work that you’re doing?

Prof. Osei: I think that a lot of people who are trained in the history of Black activism are interested in Black life, culture, and history, but they arrive primarily through the space of Black activism. And that is good, but as I was saying earlier, it trains your mind to expect certain things. What I love about history is it always reveals to you how messy we are and how chaotic we are. So I have found some things in the archives that I was like, ‘Wow! This is salacious.’ And I know why nobody has written it out.

You know, there’s a part of Black Studies that is very critical of the whole category of human itself and as it relates to Black people, but I find the messy aspects of how human beings have lived their lives really affirming. It demonstrates to us how full of life people were.

So, especially with activism, it’s like we either have to be respectable, we have to be militant, we have to do all of this self-fashioning. But when you’re able to peel out the layers, you see debates, you see people arguing, you see people clowning each other, you see people talking about their sex lives, what brings them pleasure, getting back at people—all of these things, making ways out of no way. I find that very inspiring. I also think, and this is something prominent in Black feminist historical methodology, it is one thing to find the stuff that is understood as the impossible.

But, you know, there’s some people who do not want to be found. And we have to deal with that.

Ninah Jackson:Could you talk about your approach to teaching and mentoring students?

Prof. Osei: As an undergraduate, I was in a program called the McNair Scholars Program. The way that I was mentored in that program informs everything that I do in terms of my teaching and my relationships with students. Because I think professors get to a point in their lives where most of us see ourselves as the keepers of knowledge, and we have to present ourselves like this. For me, I was just like, that’s too much pressure. I just want to be myself, and, you know, I feel like I’m a goofy person, but also just the way that I think: when I’m trying to explain something, I have to do labor that some of my colleagues don’t have to do because I don’t teach American history.

Everybody does not have the American songbook, for lack of a better word, when I’m teaching about Mexico or Brazil or Argentina or Cuba. So I have to make it relevant to them. That’s why I like using pop culture. It’s why I like thinking about history as drama, because otherwise you don’t care about it if it’s just dry facts and whatever.

It’s like what Toni Cade Bambara says. She’s talking about revolution, but I think about this with my pedagogy. She says, ‘We have to make the revolution irresistible.’ How is education supposed to be irresistible, especially in a context in which you are at an institution that is focused on professionalizing you?

Ninah Jackson: Next semester, you’ll be teaching Black Women’s History! What’s a little sneak preview of what students can expect in the course? Aso what motivated you in developing and offering this course here at Bucknell?

Prof. Osei: I read the BSU letter. I was hired as part of a cluster hire for people who did studies of race, particularly the Black experience, so I was hired to develop courses on Black people.

My first year, I had developed courses on Latin American history specifically, and I do teach about Black people and Black women in those courses, of course, but I wanted a course specifically about Black women. I had taught this course in a different format at the University of Illinois. That class was full. I was not expecting that!

So seeing the BSU letter calling for ‘we need more Black faculty to teach related to the Black experience,’ I was like, okay, this is a good time to show up and show up.

So, let me go back: why am I teaching it?

I want to teach students that Black women have a history. That we are not just adjacent to Black men. We are not footnotes to Black men. And I say that lovingly. That the reason why they feel alienated from this notion of Black women as political subjects, as historical subjects, is on purpose. Teaching them the methodology of how we study Black women’s history. And third, because I want y’all to be historically literate.

Every year I get somebody saying, ‘Oh, I saw on TikTok that back in the day during Jim Crow white people would feed Black babies to alligators.’ Look, I understand, given that this is a country that lynched people, but the alligator baby thing did not happen. And it is hard to convince people that it didn’t happen because we know everything else that happened. So I want to equip students…you don’t have to be a history major, but I want to equip you with the knowledge and the tools.