About the Author: Ninah Jackson is a junior at Bucknell University, double-majoring in Education and Critical Black Studies. In addition to being an intern with the Griot Institute, she is the Chief of Staff of the Black Student Union, a Humanities Fellow, and a co-facilitator of the Social Justice Learning Community course.

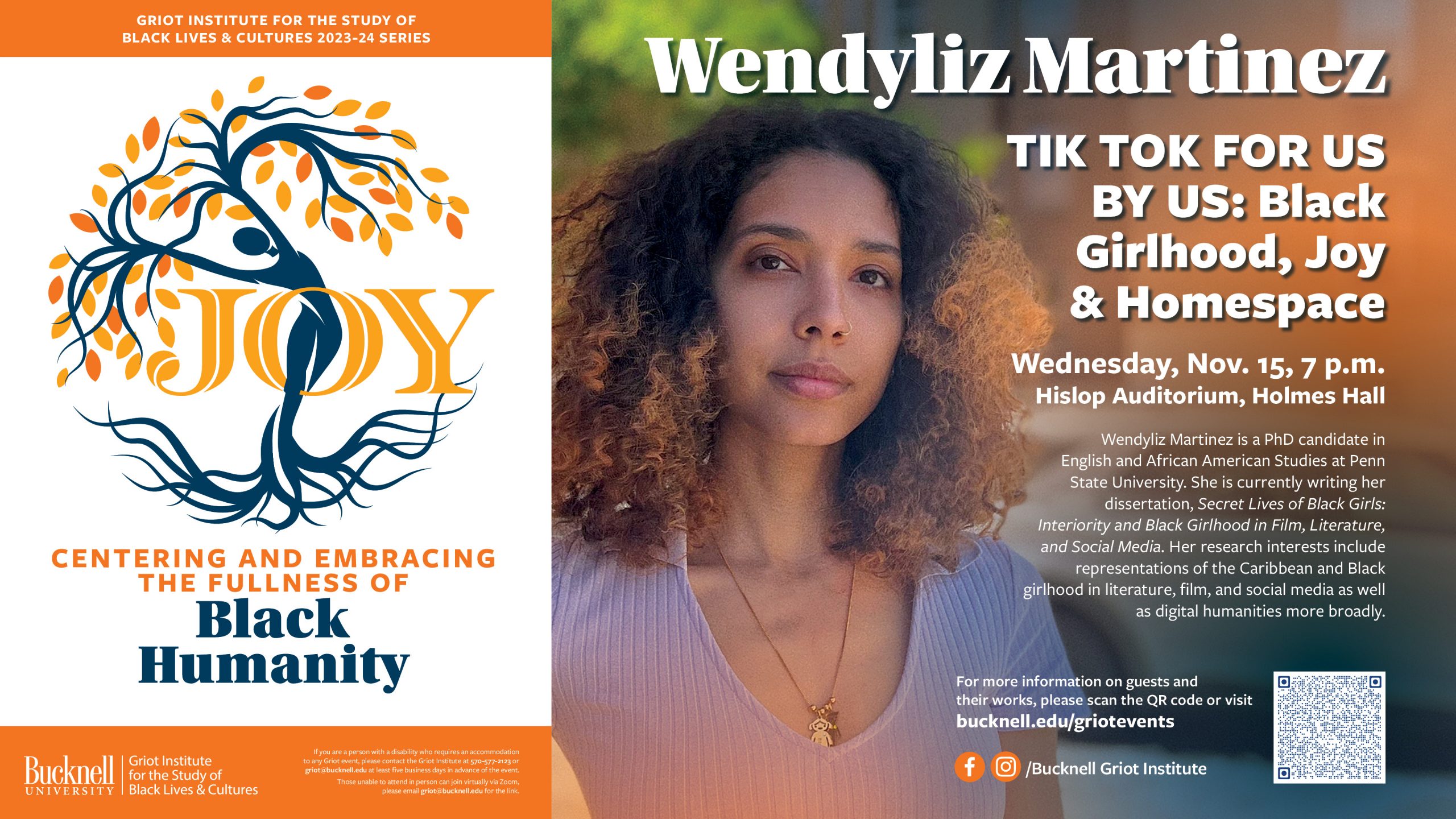

As a precursor to the 2023 Griot Spring Lecture Series – Joy: Centering and Embracing the Fullness of Black Humanity – Wendyliz Martinez, a PhD Candidate in the English and African American Studies at Penn State, joined the Bucknell community for a guest lecture entitled “TikTok For Us By Us: Black Girlhood, Joy, and Homespace” on Wednesday, November 15, 2023.

Prior to her lecture, I had a chance to chat with Martinez about her scholarship on representations of Caribbean and Black girlhood in literature, film, and social media, as well as her book chapter titled “TikTok for Us by Us: Black Girlhood, Joy, and Self-care.” Enjoy!

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

Ninah Jackson: Could you introduce yourself to folks in whatever way that means to you and whatever aspects of your life, your work that you find pertinent to include?

Wendyliz Martinez: Thank you for taking the time to interview me. My name is Wendyliz Martinez, and I am a PhD Candidate at Penn State University in English and African-American and African Diaspora Studies dual title program.

I’m also a mom of 2 children and right now my dissertation that I’m working on is titled “The Secret Lives of Black Girls: Black girlhood and Interiority in Film, Social Media and Literature.” So I kinda dive into representations of girlhood in the US and in the Spanish-speaking Caribbean. So, for now, Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic. And I kinda compare those representations to girlhood in the digital space and how we’re, you know, receiving all of that information now directly from Black girls.

Ninah Jackson: I’m interested in understanding why and how you arrived at your academic interests or chose your respective fields of study. Could you please share more about what influenced these choices and what led you to pursue the programs you are currently enrolled in?

Wendyliz Martinez: So, I guess when I first went into college for undergrad, I really didn’t have a sense of why. Like, I just knew I wanted to go to college, and I went to City College. Initially, I wanted to go to art school and got into photography programs in New York. I was planning to pursue photography, but then I realized how expensive it was to attend photography programs at places like Pratt. I didn’t want to go into debt, so I decided to go to City College, a CUNY commuter school. Since I lived with my mom and my grandma, I could stay close to home. However, I was undecided and took a variety of courses based on my interests.

In one of my courses, an introductory English class, we read “The Black Jacobins” and an excerpt from a book called “Things of Darkness.” The professor noticed my writing style during office hours and suggested I look into literary criticism. I was intrigued and started my journey to graduate school.

I began seeking programs to learn more about literary criticism, and there was Mellon Mays at City College. I applied and was eventually accepted, which provided some preparation for graduate school, understanding the application process and expectations. I continued seeking similar opportunities, participating in CUNY Pipeline, which is reserved for CUNY students across all campuses. Now, I’m a coordinator of the Cooper-DuBois mentoring program, open to undergraduates from any institution with an interest in literary studies or African American studies. This is how I got introduced to Penn.

Ninah Jackson: Could you please provide more insight into what led you to consider the representations of Caribbean and Black girlhood in media?

Wendyliz Martinez: In English class, I was used to reading classics like Jane Austen and Charles Dickens. So, literature that I didn’t feel represented in at all. I remember my senior year of high school, the only thing we read that I somewhat connected to was “When I Was Puerto Rican,” I think it was a memoir.

When I got to college, I saw introductory courses in Caribbean studies in my listings. It was a Black Studies course, and I thought, “Oh, I want to take this.” Being in that class was mind-blowing. I had never taken a class where we discussed Blackness in the Caribbean, including the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Brazil, and a bit of Latin America and Honduras, discussing Garifuna culture. It opened up a world I hadn’t been exposed to before. I felt seen because I saw things my family did culturally represented in class. This sparked my interest in seeking more and delving into Black Studies in general.

The Black Studies department at City was rebuilding as it had gone from being a department to a program. Despite fewer course listings, after that class, I was determined to take any and all classes offered by Black Studies. I got interested and took a Harlem Renaissance class, which formed the basis of my initial research interests.

In a conversation with a professor about my interest in doing a research project on “Americana” by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, I was advised to focus on older works with more scholarship. I didn’t like that advice, but I eventually crossed paths with Vanessa Valdez, a professor at City. She inspired me with her work in the Caribbean, and I became interested in queerness and representations of girlhood in Caribbean literature by Black women.

As I got into Penn State, I took a girlhood studies class, realizing that this was a field I could pursue. It expanded my research interests. I was used to seeing other kinds of childhoods represented in literature, and I couldn’t connect to living in a castle. Knowing there was literature out there representing lives like mine, and that I could research and write about it, opened up and guided me towards my dissertation.

Ninah Jackson: I think this is a really good segue to think about the book chapter you wrote for Tik Tok Cultures in the United States called “Tik Tok For Us By Us: Black Girlhood, Joy, and Self-Care.” I know that in this chapter you discussed the idea of TikTok as a platform for Black girlhood, joy and also self-care. Could you elaborate on how TikTok helps facilitate some of these things, and also, what inspired you to explore this topic?

Wendyliz Martinez: So, I’ll start with what inspired me because then I can speak to TikTok as a platform for joy and kind of self-care. I began this research during my girlhood studies class. This is when I started thinking about girlhood as a category to analyze. In the literature I had been writing about in undergrad and what interested me in grad school, they did center black girls. Whether queer, Dominican, Puerto Rican, American, etc. They encompassed different identities, but I never thought to center the age part of it. I considered sexuality and race but didn’t necessarily focus on age. That class opened up the idea of age as a category to analyze, part of your intersecting identities that include race, sexuality, class, etc. Children, as bell hooks articulates, are part of this oppressed and marginalized group. The class introduced that perspective to me.

In the middle of the class, COVID happened, and the pandemic hit. I found myself on TikTok, which had become a thing for me personally. It had always existed, but it didn’t catch my attention until then. One of the girls I interviewed provided a history of TikTok, schooling me a bit on what was going on. It wasn’t until COVID that TikTok came onto my radar. I started scrolling my “For You” page. Having previously taught high school before grad school, many of my colleagues were discussing moving online to teach on Zoom and other platforms. It was a strange time, as you likely remember. During this period, all these girls, including myself, were dealing with the challenges of online classes. Personally, I had to attend classes online with my son in the room because we couldn’t go outside due to the lack of childcare. Thankfully, it was just me, my partner, and my child. He would attend classes with me, and I also heard about the experiences of my former colleagues. My mom, too, is an educator.

She would talk about how these kids…you know, parents have more than one child. Many families have more than one child. All these people are in this space together, having to do these things. And it’s like, where do you have privacy? Where do you have the time to have fun? How do you escape the chaoticness of being around so many people and having to do so many things? That kind of inspired me. Once I started seeing these TikToks of girls, when they’re dancing—like when the “Renegade” was very popular—I thought, “Oh, this looks amazing. And this looks like a place where, amongst the chaos, at least, you have your little platform where you can do some things that bring you a little bit of joy in a time that was so uncertain.” People were always talking about uncertain times. We don’t know what’s going to happen. We’ve never been through this before—at least, the generations that were living through this.

So, I saw TikTok as that kind of space where these Black girls were able to do things. They would do hair care routines. Based on the interviews I was conducting for that chapter, they also spoke about the ability to make their page private. That’s a general feature across platforms, but because I decided to focus on TikTok, that aspect came up. The ability to have your friends up there or only make drafts. It becomes almost like a virtual diary where you can do little routines, and you don’t have to put it out there to be scrutinized by others. Even though that probably happens all the time in person, online, in different spaces, cyberbullying, real-life beliefs, and all those things.

Ninah Jackson: What are some of the challenges that Black girls encounter when navigating and using TikTok, but also how do they overcome those presented challenges?

Wendyliz Martinez: The challenges of platforms or spaces that aren’t really made for you in a sense, like, in general, all these apps and websites are made by people who aren’t taking into consideration race, class, gender, sexuality, etc. So, there’s a lot of oversight, oversight of harassment that black women and black girls face on these platforms. There’s co-opting, a lot of appropriation of dances, like the Renegade, for instance. White girls, teens, or women appropriate these dances and get all the media attention. They might get invited to Jimmy Fallon or other shows, getting the spotlight for something they didn’t create. So, these challenges arise because these apps are not made for Black girls. I don’t know who their target demographic is, but most likely, it wasn’t a little Black girl that they had in mind when creating these algorithms and coding.

With that idea that this is not necessarily a space made for you, you’re going to go through things like bullying, harassment, hypervisibility where your content can go viral, opening up a whole can of worms. That’s why many girls I interviewed mentioned having private pages. They don’t want anybody taking their videos and using them in ways they don’t want. In the article itself, I delve more into parent surveillance and how parents monitor their children’s content creation. There’s also a discussion about the ways girls subvert this surveillance, like making their page private or saving content to their phones and deleting it from their public page. One girl even talked about posting something, then deleting it if her parents didn’t like it, but it was already saved. These are the subtle ways that girls express agency and autonomy, those little invisible actions that we might not be aware of.

Ninah Jackson: You start the article discussing the murder of Ma’Khia Bryant. I would appreciate it if you could share a bit about the choice to frame the piece around that specific incident and how it connects to the utility or usefulness of TikTok.

Wendyliz Martinez: I’ll start by explaining why I chose to open the piece the way I did. The longer version, which wasn’t published, delved into the concept of Black suffering, particularly within the context of COVID. I discussed how Black people were experiencing higher rates of death and various impacts compared to other groups due to the pandemic.

In the midst of the pandemic, we learned about the tragic murder of Ma’Khia Bryant. What caught my attention besides the incident itself was the social media response, not focusing on videos depicting the events leading to her death but instead sharing her TikToks. These TikToks showcased her doing hair care routines and exuding joy, revealing aspects of her life that weren’t defined by victimization or oppression. It highlighted the resilience to find joy despite a system designed to oppress and create suffering.

This resonated with me because it underscored that despite these oppressive systems, individuals can assert their joy and refuse to let it be stolen. It became evident that even in the face of immense challenges, one can still find moments of joy. This perspective guided my thinking, shaping the narrative around Black joy in the midst of suffering.

This led me to contemplate how TikTok becomes a platform where individuals can subvert the intentions of systems that seek to oppress.

Ninah Jackson: Have you considered the future impact of TikTok on Black girlhood and what changes or developments you foresee in terms of Black representation, specifically in Black girlhood?

Wendyliz Martinez: So, it’s interesting because I think we’re all witnessing the development, or rather, evolution of TikTok. Initially, it attracted regular people doing everyday things, presenting a contrast to platforms like Instagram, where influencer culture was dominating. However, TikTok is undergoing a shift towards more influencer-type content, showcasing luxurious lifestyles that may not align with the reality of many creators.

This shift seems to be influenced by a post-pandemic mentality where there’s a push to return to normalcy, even though there’s a visible pushback against that narrative, as seen in movements like the one for Palestine. During the pandemic, there was a trend of focusing on Black voices and DEI initiatives, but the challenge lies in sustaining this focus beyond trends and not succumbing to capitalist motives.

Despite the complexities, there’s a glimmer of hope, especially as the popularity of online platforms allows for real-time visibility of societal shifts. Even amid systemic attempts to revert to harmful practices, there’s a notable pushback, and the immediacy of online communication facilitates the collective recognition that we don’t have to return to old ways.

In this context, I’m exploring the representation of girlhood for my dissertation chapter, specifically focusing on how Black girls are taking center stage in creating and sharing content within their community. They are becoming the voices that we listen to and relate with, offering a more authentic representation of their experiences. While delving into meme culture and related topics, I’m still contemplating the nuances of what I want to convey. Ultimately, my hope, driven by an Afro-Futurist perspective, is that girls will continue to be the voices we center moving forward.