About the Author: Ninah Jackson is a junior at Bucknell University, double-majoring in Education and Critical Black Studies. In addition to being an intern with the Griot Institute, she is the Chief of Staff of the Black Student Union, a Humanities Fellow, and a co-facilitator of the Social Justice Learning Community course.

“What is joy? What is joy? I tend to describe joy as this experience of transformation or release from the constraint or costume of the individual or the subject into this other form. So, for me I think it’s about floating, it’s about being nothing and being everything at the same time; this sense of the self disappearing in the context of the vastness of the earth, the ocean, the sky, the land. That kind of joy is always about self-dissolution, escape.” – Saidiya Hartman

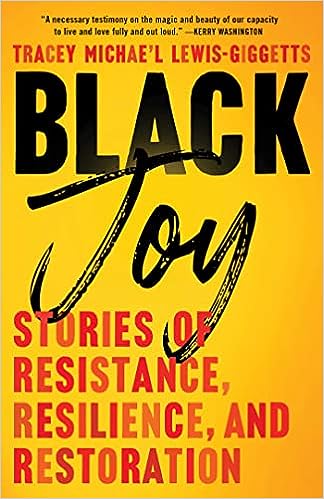

In the pursuit of joy, we often find ourselves on a journey of self-discovery and transcendence…sometimes a journey of undoing and unraveling too. As such, the concept of joy – but especially Black joy – poses a profound question: what exactly is it? This provocative, yet seemingly simple question emerged as the cornerstone of the Griot Institute’s book group discussion on Black Joy: Stories of Resistance, Resilience, and Restoration by Tracey M. Lewis-Giggetts.

Monday’s group discussion was facilitated by Griot Intern Ryleigh Roberts and accompanied by Rev. Angela Jones, the Rooke Chapel’s 2023-24 Gospel Music Fellow. To ground the conversation ahead, Rev. Jones graced those of us in attendance with an excerpt of a soul-stirring song and provided reflections on the connection between Gospel music and Black joy: a corporeal, emotional, and spiritual experience, Gospel has historically served as a “moment of reflection,” “source of hope, strength, and consistency,” and conduit of “introspection” for Black people and Black communities. For Jones, Gospel is a musical and sonic manifestation of Black Joy itself.

Other discussants characterized Black Joy as inherently entangled in and bounded with our broader social, historical, and political fabric. One attendee asked pointedly, “[h]ow can we understand the radical role of joy without understanding the trauma?” Another noted the difficulty of “resting” while others struggle under the brunt of harmful personal and systemic conditions: “the need to make sure others make it through is a big weight,” they shared.

Eventually, our discussion and collective inquiry was localized to the Black student experience here at Bucknell. How have Black students found or created Black Joy? How have Black students engaged in placemaking and cultivated belonging? How has the joy of Black students been constrained or inhibited? What is the relationship between Bucknell and Black Joy?

These lines of inquiry gave rise to another key characteristic of Black Joy: it is an opportunity to exist in one’s “fullness of self,” meaning we can only experience Black Joy as we define it for ourselves – on our terms. So…what say you? What does Black Joy look like, feel like, smell like, and sound like to you?